Ten years ago, little was known about gut health, but scientists now understand it plays an essential role in preventing and reducing a wide range of diseases – from bowel cancer to depression. So, what exactly does gut health mean, and how can a veg~n diet hold the key to better health outcomes, just by influencing the bacteria that live in our gut?

What is meant by gut health?

The term ‘gut health’ describes the function of the entire digestive tract; from eating and digesting our food, through to defecation. Our gut performs three main functions:

- Immunity: With 70% of our body’s immune cells in the gut, it plays an important role in regulating our immune response to alleviate disease.

- Digestion. Our gut is critical to breaking down the foods we eat into small molecules that can then be absorbed and used by our body’s cells.

- Gut microbiota. The trillions of microbes living in our gut that perform various roles attributed to improved health outcomes. This is what most people refer to when talking about ‘gut health’ and will be the focus of this article.

Gut microbiota

The term gut microbiota refers to the bacteria, fungi and viruses that live in the lower part of our digestive tract. This community of microbes interacts directly with our brain, heart, lungs, and skin, to help prevent and manage disease in these parts of the body (Varela-Trinidad et al., 2022).

The gut microbiota has a varied role that includes: helping our immune response; regulating blood sugar and blood fats; regulating appetite; and making specific vitamins, amino acids and hormones (Rossi, 2019; Varela-Trinidad et al., 2022). Our gut microbiota has been linked to a range of disorders, including depression and anxiety, Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, acne, asthma, heart failure, obesity and type 2 diabetes (Varela-Trinidad et al., 2022).

Every type of microbe performs a different function. Depending on the microbe and the environment within our gut, the gut microbiota can be beneficial to health, or it can contribute to poorer outcomes. A healthy gut environment is one that is balanced with a good proportion of beneficial microbes, and is associated with better health outcomes for the conditions noted above. The composition and function of our gut microbiota is determined by our diet, genes, environmental factors, and medications.

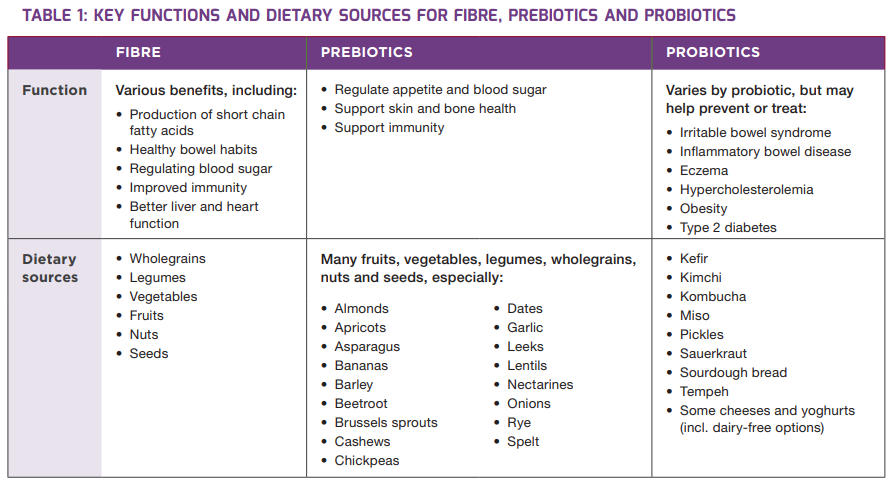

The good news is we can directly influence the proportion and diversity of beneficial gut microbes through a healthy diet and regular physical activity (Khalesi et al., 2021; Koponen et al., 2021). One of the best ways to improve microbiota function is through a varied diet containing minimally processed plant foods, such as fruits and vegetables, wholegrains, legumes (beans, peas and lentils), nuts and seeds. These provide an excellent source of dietary fibre, prebiotics and probiotics, which are essential for a healthy gut environment (Anderson-Haynes, 2021; Asnicar et al., 2021).

Dietary fibre

Dietary fibre is possibly the best way to influence the gut microbiota. The gut microbiota break down dietary fibre to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which limit the growth of some harmful bacteria (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2023). SCFAs are responsible for promoting healthy bowel habits, balancing our blood sugars, activating the immune response, and for healthy liver and brain function, among other things (Rossi, 2019).

The Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand recommend that adults consume 25-30 g of dietary fibre each day (National Health and Medical Research Council et al., 2006). In reality, the average fibre intake for New Zealand adults is 20g per day (Ministry of Health, 2020). Intakes are highest in vegans and vegetarians, respectively, who consume up to 1.5 times the amount of dietary fibre as omnivores (Clarys et al., 2014; Dawczynski et al., 2022).

The best sources of dietary fibre are: fruits, vegetables, wholegrains, legumes, nuts and seeds.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are foods that feed specific bacteria in our gut. Prebiotics are typically complex carbohydrates that our bodies cannot digest, but our beneficial bacteria like to eat (Rossi, 2019). Prebiotics promote the growth and functioning of probiotics.

Prebiotics have a role in regulating our appetite and blood sugar; supporting bone health and skin health; and in supporting our immunity (Rossi, 2019).

Many fruits, vegetables, wholegrains, legumes, nuts and seeds are good prebiotic sources; but especially the following: almonds, apricots, asparagus, bananas, barley, beetroot, brussels sprouts, cashews, chickpeas, dates, garlic, leeks, lentils, nectarines, onions, rye, and spelt.

Probiotics and fermented foods

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when consumed in adequate amounts, will have a health benefit (FAO/WHO, 2002). They consume prebiotics and interact with the gut microbiota to have a beneficial effect in the gut environment.

The exact function of probiotics varies according to the type and amount of probiotic consumed. There is some evidence that they can help prevent or treat irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, eczema, high blood cholesterol, obesity, and diarrhoea caused by antibiotics (National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements, 2022).

Probiotics are naturally present in fermented foods, such as yoghurt and sauerkraut. They are also sometimes added to other food products and are available as dietary supplements. Common types of probiotic include Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium.

Fermentation is traditional method of preserving food. It Involves the use of microbes to convert the sugar and starch in a food to transform it into something else. Many (but not all) fermented foods contain probiotics.

Probiotics must be consumed alive to have health benefits. The amount of live probiotics in a food is affected by the processing and storage of that food, and how it is digested by our body. Any food product that is exposed to variances in temperature, acidity, oxygen content and moisture content may lose some or all of its probiotics (Terpou et al., 2019). For example, the heat treatment used when pasteurising milk and yoghurt will kill probiotics, unless those foods contain specific resistant probiotic strains. Furthermore, the probiotics in some foods may not survive passage through the acidic conditions of the stomach to reach the gut (National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements, 2022).

Common fermented foods that contain naturally occurring or added probiotics include: kefir, kimchi, kombucha, miso, pickles, sauerkraut, sourdough bread, tempeh, and some cheeses and yoghurts (including dairy-free options) (Harvard Health Publishing, 2023).

Veg~n diets and gut health

Veg~n diets are ideal for optimal gut health and overall health outcomes because they usually include a high quantity and broad range of minimally processed plant foods. They are typically a good source of fibre, prebiotics and probiotics (Sidhu et al., 2023).

Scientists have found that people who eat at least 30 different types of plant food per week have the most diverse gut microbiota (McDonald et al., 2018). This means a varied colony of health-promoting bacteria in the gut and better range of benefits in preventing and managing disease.

Conclusion and recommendations

- Gut health is an emerging and interesting area of research. There is still more to learn about the exact role and function of specific gut microbiota and their role in health.

- Whatever diet you follow, the best way to optimise gut health is to eat more wholegrains, fruit, vegetables, legumes, nuts and seeds that are minimally processed.

- Having a diversity of plant foods is important, and a great reason to have fun trying new foods. Aim to eat at least 30 different sources of legumes, wholegrains, fruit, vegetables, nuts and seeds each week. This can include fresh, frozen, dried or canned products. Don’t worry too much about measuring portion sizes, but focus on the variety of foods.

- Note that a high intake of prebiotic foods, especially if introduced suddenly, can cause gas and bloating. If you have gastrointestinal sensitivities, such as irritable bowel syndrome, introduce prebiotics in small amounts to assess your tolerance (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2023).

- Be aware that antibiotics work by targeting and killing bacteria. They will kill off both harmful and beneficial bacteria in your gut. If taking antibiotics, ensure your diet is rich in probiotic food sources and talk to your health professional about whether a probiotic supplement is also needed.

- If you’re following a healthy, balanced diet and are in good health, a probiotic supplement shouldn’t be needed.

- Note that probiotics can die off due to processing or long shelf life, which means the health benefits are lost. When shopping, look for products labelled as “contains live cultures”, and for products with at least one billion Colony Forming Units (CFUs) per serve at the end of the product’s shelf life, not at the time of manufacture (National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements, 2022).

By Catherine Lofthouse

Catherine Lofthouse is a passionate plant-based foodie who loves to explore all things related to veg~n living. She is also a registered dietitian.

For more articles, become a NZVS Member to receive our quarterly magazine, Vegetarian Living NZ. Click here to find out more.

References

- Anderson-Haynes, S.-E. (2021, April 21). Diet, disease, and the microbiome. Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu...

- Asnicar, F., Berry, S. E., Valdes, A. M., Nguyen, L. H., Piccinno, G., Drew, D. A., Leeming, E., Gibson, R., Le Roy, C., Khatib, H. A., Francis, L., Mazidi, M., Mompeo, O., Valles-Colomer, M., Tett, A., Beghini, F., Dubois, L., Bazzani, D., Thomas, A. M., … Segata, N. (2021). Microbiome connections with host metabolism and habitual diet from 1,098 deeply phenotyped individuals. Nature Medicine, 27(2), 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591...

- Clarys, P., Deliens, T., Huybrechts, I., Deriemaeker, P., Vanaelst, B., De Keyzer, W., Hebbelinck, M., & Mullie, P. (2014). Comparison of nutritional quality of the vegan, vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian and omnivorous diet. Nutrients, 6(3), 1318–1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6031...

- Dawczynski, C., Weidauer, T., Richert, C., Schlattmann, P., Dawczynski, K., & Kiehntopf, M. (2022). Nutrient Intake and Nutrition Status in Vegetarians and Vegans in Comparison to Omnivores—The Nutritional Evaluation (NuEva) Study. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/ar...

- FAO/WHO. (2002). Guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food. Joint FAO/WHO Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food, 1–11.

Harvard Health Publishing. (2023, July 26). How to get more probiotics. Harvard Medical School. https://www.health.harvard.edu...,sourdough%20bread%20and%20some%20cheeses. - Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (2023). The Microbiome. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/n...

- Khalesi, P., Saman, Vandelanotte, P., Corneel, Thwaite, Bs., Tanya, Russell, P., Alex M. T., Dawson, P., Drew, & Williams, P., Susan L. (2021). Awareness and Attitudes of Gut Health, Probiotics and Prebiotics in Australian Adults. Journal of Dietary Supplements, 18(4), 418–432. CINAHL Ultimate. https://doi.org/10.1080/193902...

- Koponen, K. K., Salosensaari, A., Ruuskanen, M. O., Havulinna, A. S., Männistö, S., Jousilahti, P., Palmu, J., Salido, R., Sanders, K., Brennan, C., Humphrey, G. C., Sanders, J. G., Meric, G., Cheng, S., Inouye, M., Jain, M., Niiranen, T. J., Valsta, L. M., Knight, R., & Salomaa, V. V. (2021). Associations of healthy food choices with gut microbiota profiles. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 114(2), 605–616. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/n...

- McDonald, D., Hyde, E., Debelius, J. W., Morton, J. T., Gonzalez, A., Ackermann, G., Aksenov, A. A., Behsaz, B., Brennan, C., Chen, Y., DeRight Goldasich, L., Dorrestein, P. C., Dunn, R. R., Fahimipour, A. K., Gaffney, J., Gilbert, J. A., Gogul, G., Green, J. L., Hugenholtz, P., … Knight, R. (2018). American Gut: An Open Platform for Citizen Science Microbiome Research. mSystems, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.1128/mSyste...

- Ministry of Health. (2020). Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults: Updated 2020. Ministry of Health. https://www.health.govt.nz/sys...

- National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, & New Zealand Ministry of Health. (2006). Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council.

National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. (2022). Probiotics: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factshe... - Rossi, M. (2019). Eat Yourself Healthy: An easy-to-digest guide to health and happiness from the inside out. Penguin Life.

- Sidhu, S. R. K., Kok, C. W., Kunasegaran, T., & Ramadas, A. (2023). Effect of Plant-Based Diets on Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review of Interventional Studies. Nutrients, 15(6), 1510. CINAHL Ultimate. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu1506...

- Terpou, A., Papadaki, A., Lappa, I. K., Kachrimanidou, V., Bosnea, L. A., & Kopsahelis, N. (2019). Probiotics in Food Systems: Significance and Emerging Strategies Towards Improved Viability and Delivery of Enhanced Beneficial Value. Nutrients, 11(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu1107...

- Varela-Trinidad, G. U., Domínguez-Díaz, C., Solórzano-Castanedo, K., Íñiguez-Gutiérrez, L., Hernández-Flores, T. D., & Fafutis-Morris, M. (2022). Probiotics: Protecting Our Health from the Gut. Microorganisms, 10(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/microo...