“Most of us know what a healthy diet looks like ...”. Ummm. Really?

There was a qualification in the rest of the sentence in a new report lambasting Aotearoa New Zealand for its appalling retail food environment.

“… but accessing it [the healthy diet] is increasingly difficult, especially for those most deprived,” concluded the statement in the report from the policy think tank, the Helen Clark Foundation.

Certainly, if any of us do know what a healthy diet looks like, the battleground that is the regular supermarket shop has raised choosing food wisely to whole new levels of difficulty. The problems are not just trying to sort healthy from unhealthy but also weighing up the benefits or otherwise of fresh and packaged, lightly processed (e.g. fermentation) and ultra-processed foods. While some of us are also navigating claims of vegetarian, vegan, plant-based, the dubious “Vegan Friendly,” and the unknowable, which may contain milk, soy, gluten, nuts, etc. All within a budget!

Few of us are trained nutritionists, and many simply follow cultural or family traditions, eating what is familiar or normal in our social context. New information is most likely gained from short news articles (the latest fad/craze/celebrity endorsement), advertisements, and the very packets of food we’re confused into buying, with their dodgy highlighted claims (low salt/low sugar/gluten-free/high fibre).

In this toxic environment, we all need help. On the upside, there is an ever-growing body of evidence and calls for action from health experts and policy wonks.

Last Spring’s edition of Vegetarian Living NZ reported the findings of the Public Health Advisory Committee’s report to the Health Minister, which showed that Aotearoa New Zealand exports enough food to feed 63 million people a day, while back home, a fifth of Kiwi kids live in households where food often runs out.

For vegetarians, probably the most startling fact was that only 4.9% of children and 6.7% of adults are estimated to eat the recommended number of daily servings of fruit and vegetables.

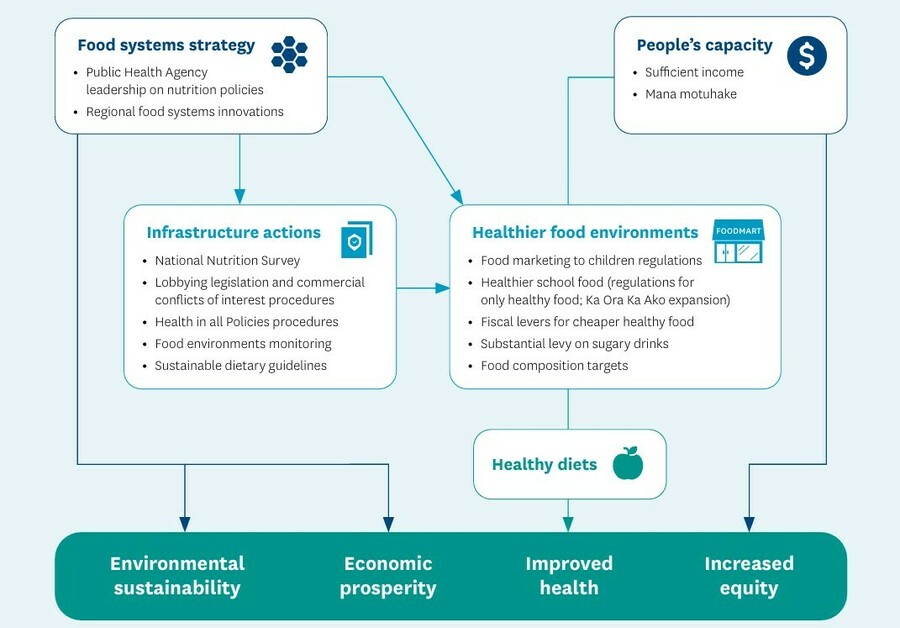

That report recommended a complete rebalancing of the country’s food system, including comprehensive action by central and local government, private enterprise, and communities.

“Right now, across our food ecosystem, things are out of balance. The health of people and the environment is not being prioritized … The flow-on effect is that only a trickle of healthy, affordable, nourishing food options are available to many people in the places they live, and a flood of unhealthy food.”

Actions prioritised by the Expert Panel for Government to improve the healthiness of New Zealand food environments

Now, the Helen Clark Foundation has added to the evidence of foul food play by suggesting a fix for the “weak rules [that] undermine health and economic growth in New Zealand.”

The High Cost of an Unhealthy Food System

The foundation focused on the shockingly high costs of obesity:

“New Zealand’s rates of obesity are among the highest in the world, and on current settings are likely to rise further. An estimated two million New Zealanders will be affected by 2038, and this comes with increased risks of many types of cancer, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and musculoskeletal conditions.

“Nearly $2 billion is spent annually on treating obesity-related diseases – which is 8 per cent of the health budget. As rates of obesity rise, more taxpayer dollars will be needed to fund the health service.”

It added that the economy was being held back to the tune of up to $9 billion in lost productivity annually, reflecting a wide range of factors, including increased healthcare costs, reduced life expectancy, lower wages, and stigma.

“We are not only becoming a sicker nation but a poorer one too.”

Doctors can attest to the ever-rising number of people with obesity-related problems. Middlemore Hospital intensive care specialist Dr David Galler told the NZ Herald how much this grim, dispiriting work increased through the 2000s.

“It was a bit like repairing broken panes of glass in a demolished building. You repair that pane of glass at considerable cost to them, their families, and the state. Three months later, the same person comes in with three broken panes. And then you never see them again because they’re dead.”

Despite such bleakness, the Clark Foundation found that few New Zealand governments have taken decisive, evidence-based steps to reduce obesity over the long term, opting instead for voluntary schemes like the Health Star rating system, industry-led approaches, or brief campaigns focused on personal responsibility. None had seriously engaged with improving the commercial food environment.

In fact, the foundation noted that the current approach to obesity policy assumes individuals can navigate a commercial food environment where unhealthy, cheap food is readily available, while healthy options are expensive and getting more so.

Just as extractive industries like mining pollute the natural environment, privatizing profits while socializing the costs of clean-ups, grocery companies contaminate the food environment while reaping substantial rewards from unhealthy food products.

“The government and taxpayers foot the costs associated with obesity to our health system and the economy,” the Clark Foundation said.

“New Zealand is one of the few developed countries without a national obesity strategy. The status quo is not working; New Zealand needs to reimagine its approach to obesity and tackle its root causes.”

Three Key Recommendations

The Clark Foundation outlined three key recommendations to address these challenges:

1. Regulation and Incentives

New Zealand needs robust, enforceable regulations that are agile enough to meet today’s challenges.

Other countries have successfully introduced sugar levies to reduce consumption.

The UK’s Soft Drinks Industry Levy (2016) led to a 35% reduction in total sugar sold in soft drinks over four years and fewer hospital admissions for childhood tooth extractions.

2. Government-Led Change

The state should lead by example in schools, hospitals, government canteens, the military, and prisons.

These institutions serve hundreds of thousands of meals daily, meaning population-wide impact is possible.

Creating healthy food environments in these spaces would reinforce social norms around healthy eating and increase demand for healthier options across the country.

3. Improved Treatment Approaches

The government should adopt new treatments to improve the prevention and management of obesity.

To be effective, individuals must return to an environment that supports good health, rather than one saturated with sophisticated marketing of unhealthy food.

Food Injustice and Te Tiriti o Waitangi

The foundation also highlighted that New Zealand’s approach to reducing obesity must align with its obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi.

“While all New Zealanders are affected by New Zealand’s unhealthy food environment, Māori are disproportionately so, being exposed to unhealthy food marketing twice as often as non-Māori and living among more unhealthy food outlets than non-Māori.

“Nearly half of all Māori live with obesity, and the rate of obesity among Māori children is six percentage points higher than for non-Māori. Further, Māori are also more likely to suffer dental caries and experience higher rates of diabetes than non-Māori.”

It added that Pasifika communities are even more affected, with 67% of Pasifika adults and 28% of Pasifika children living with obesity.

A Call to Action

The report concluded that the Government has a duty to protect public health and must take bold action to tackle obesity.

“If implemented effectively and supported by an enduring cross-party consensus, a new approach to preventing obesity will substantially improve health outcomes in New Zealand, while driving productivity and allowing businesses to grow.”

Finally, the foundation called on politicians to take responsibility for the health of future generations:

“Those who act will leave proud legacies – having protected the health of our nation, the future of our children, and the strength of our economy.”

By Philippa Stevenson, a Waikato-based vegan journalist

For more articles see our quarterly magazine Vegetarian Living NZ.

Reference:

“Junk Food and Poor Policy? How weak rules undermine health and economic growth in New Zealand and how to fix it” The Helen Clark Foundation.